Breadcrumbs

- Home

- MD/PhD Program

- News

- Putting “I-You” into Medical Practice

Putting “I-You” into Medical Practice

Liam Mitchell

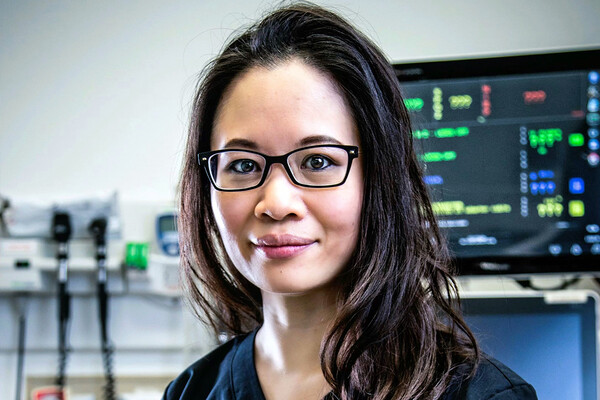

U of T medical students Atara Messinger and Benjamin Chin-Yee have turned to the work of 20th-century philosopher Martin Buber to find new insights for physicians. They shared their insights in a paper published in Medical Humanities entitled “I and Thou: learning the ‘human’ side of medicine,” which was recently recognized with the 2016 Essay Prize from the European Society for Person Centered Healthcare. Messinger and Chin-Yee spoke with writer Liam Mitchell about their work and the lessons Buber has for today’s doctors.

U of T medical students Atara Messinger and Benjamin Chin-Yee have turned to the work of 20th-century philosopher Martin Buber to find new insights for physicians. They shared their insights in a paper published in Medical Humanities entitled “I and Thou: learning the ‘human’ side of medicine,” which was recently recognized with the 2016 Essay Prize from the European Society for Person Centered Healthcare. Messinger and Chin-Yee spoke with writer Liam Mitchell about their work and the lessons Buber has for today’s doctors.

Martin Buber might be well known to philosophy majors, but probably not as well known to most medical students. What led you to his work? You argue that Buber’s philosophy of dialogue "raises fundamental questions about how human beings relate to one another, and can thus offer valuable insights into the nature of the clinical encounter.” How so?

We were drawn to Martin Buber because we feel that his “philosophy of dialogue” offers important lessons about the doctor-patient relationship. In I and Thou (1923), Buber argues that there are two basic modes of human interaction: the “I-It” and the “I-You.” For Buber, the I-It is an interaction between two beings that resembles a subject-object relationship. It is a “detached” interaction in which the “I” sees the other as an object that is “describable, analysable, classifiable.” The I-You, on the other hand, is a dialogical relationship in which people encounter one another in their holistic existence. In an I-You interaction, the “I” sees the other as a “whole being” that is greater than the sum of its component parts: “as a melody is not composed of tones, nor a verse of words, nor a statue of lines—one must pull and tear to turn a unity into a multiplicity—so it is with the human being to whom I say You.”

Buber’s work serves as an important reminder that in today’s subspecialized medical model, it can be easy to engage in purely “I-It” relationships with patients: to see patients not as whole beings with life stories, but as collections of organ systems with individualized functions. Buber acknowledges that it can be tempting to exist solely in the realm of the I-It; indeed, the I-It is an ordered world where one “can live comfortably,” whereas the I-You “pulls us dangerously to extremes, loosening the well-tied structure, leaving behind more doubt than satisfaction, shaking up our security.” Although I-You moments in medicine—where we allow ourselves to step into the life-world of our patients and see our patients as “whole beings”—can serve as jarring reminders of our patients’ suffering and of our own fallibility, Buber reminds us that these moments inject a critical dose of meaning and humanity into the clinical encounter. Overall, Buber’s work captures an inherent tension in clinical medicine. Ultimately, medicine requires a certain amount of scientific objectification, yet a medicine that exists solely in the “I-It” threatens to lose its humanity. As Buber warns: “without ‘It’ a human being cannot live. But whoever lives only with that is not human.”

You explore Buber’s perspective through literature (Leo Tolstoy's Ivan Ilych) and theatre (Margaret Edson's Pulitzer Prize winning play, Wit). How does philosophy, literature, drama and other disciplines in the humanities contribute to better health care?

This is an important question. We both have personal interests in the humanities and feel that philosophy, literature, and other arts-based disciplines enrich our lives in general. But our passion for the humanities and social sciences, and our advocacy for their role in healthcare, goes beyond this implicit conviction that reading makes us more reflective and sensitive people; we also believe it makes us better doctors.

Although medicine in the twenty first century has grown dramatically in its scientific and technological advancements, few would disagree that at the heart of medicine lies the human interaction between doctor and patient. Questions explored in philosophy and literature—questions about the human condition, happiness and suffering, life and death—have obvious relevance to medicine, and are encountered on a day-to-day basis in clinical practice. In addition to dealing with these universal questions, the humanities also allow us to grasp the particular—the local and contextual. They provide unique access to the “other,” allowing us to enter another “life-world.” For this reason studying literature is often seen as a means of fostering empathy as well as cultural sensitivity. In medicine, narrative and interpretive skills that enable practitioners to grasp the particular and appreciate context are essential to developing clinical judgment, which goes beyond the simple application of biomedical knowledge or abstract “evidence.” Thus in addition to enriching our personal lives, the humanities allow us to bring an enhanced sense of compassion, curiosity and creativity to our work with patients.

Do you think we are doing enough in U of T Medicine to incorporate lessons the humanities can offer into our MD curriculum? If not, what more can we do?

One question we have both wondered about is whether medical education systems today are doing enough to teach medical students about the “human” side of medicine. Medical curricula seem to be doing an excellent job of preparing us to become competent diagnosticians, but are they doing enough to help us become humane caregivers?

We are thrilled to see that the medical humanities are gaining increased traction in medical schools worldwide. At U of T, we’ve had the privilege of benefitting from opportunities, both curricular and extracurricular, that have allowed us to explore and engage in medical humanities initiatives while in medical school. The U of T Health Arts Humanities Program, for instance, offers arts-based learning initiatives including storytelling and narrative medicine workshops, as well as various programs that foster a deeper understanding of health and illness through cinema, theatre and fine art. U of T Medicine’s newly launched medical humanities blog—ArtBeat—serves a space where medical students can share original writing samples, and can access the Companion Curriculum—a set of poems, short stories and other literary works that were hand-selected to complement and enhance the biomedical curriculum. Moreover, the new curriculum at U of T seems to be moving toward a more integrated model of medical education that emphasizes not only the “medical expert” role, but other CanMEDS roles including communicator and health advocate. Within the new curriculum, there are now lectures that provide an introduction to philosophy of medicine, covering topics from epistemology to ethics. This is a great start to the bridging of various disciplines, and reinforces the notion that the lessons the humanities and social sciences have to offer are as integral to the practice of medicine as the pure biomedical science.

You earned an award for your paper. Tell us about the award and what did it mean to you?

It was a great surprise and honour to learn that our essay “I and Thou: Learning the ‘Human’ Side of Medicine” was awarded the 2016 Essay Prize from the European Society for Person Centered Healthcare (ESPCH). The ESPCH is a multi-disciplinary body made up of clinicians, academics, policymakers and patients which aims to promote the re-personalisation of health services and refocus care on the wider effects of disease on patients’ lives and social functioning. We were thrilled receive recognition from the ESPCH and to help further their mission of promoting person-centered care.

News